We began our discussions into Open Science in our last post, looking at where, as researchers, you can store and gain access to data through online repositories. But before we have data to deposit it’s important to understand where those numbers have come from. Enter stage left, protocol preregistration, something that doesn’t happen too often in Gait and Posture research (at least not yet!) but a key ingredient changing how research is conducted in a number of fields. In this edition, we delve into what preregistration means and how you can take part. But first,

Is exploratory a dirty word in science?

In a study on the role of hypothesis testing in biomechanical research, Rowbottom & Alexander (2012) found that “…whereas no papers had exploration as a stated aim, 58% of papers had hypothesis testing as a stated aim. [they] had strong suspicions, at the bare minimum, that presentational hypotheses were present in 31% of the papers in this latter group.” While this may not always be problematic, it can certainly be, as statistics simply do not hold up when hypothesis testing occurs after the results are known. It’s such an issue that it now comes with its own acronym, HARKing.

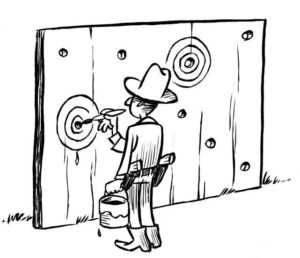

With HARKing, you can always hit the bullseye! Figure courtesy of Dirk-Jan Hoek, used under CC 2.0 / original was cropped.

One of the solutions to prevent HARKing? The preregistration of a study protocol, including the expected analyses and statistical tests to be conducted on your primary outcome measure. This can be done in one of two ways; 1) preregistration, in which you put a protocol online, and can later refer to this when reporting the results of your manuscript, and 2) registered reports, in which manuscripts are examined in two stages, where an initial protocol and analysis is accepted by the journal, prior to data collection and re-examined following a full write-up.

We can take the world of clinical trials as a perfect example of preregistration in motion. Preregistration of primary outcomes in clinical trials (on ClinicalTrials.gov) has been required since 2000. Interestingly, in a review paper evaluating drugs or dietary supplements for the treatment or prevention of cardiovascular disease (Kaplan & Irvin, 2015), this has been shown to have a drastic effect; studies before the year 2000 showed much larger effect sizes, while after 2000, the number of studies that reported significant effects drastically decreased. While it may indeed be so that the interventions that were proposed before 2000 were more effective, it is more likely that this finding suggests “fishing” for significant findings pre-2000. As such, this example nicely illustrates why it may be good to preregister studies when they are designed to test the hypothesis.

In a similar fashion, and spurred by their own replication crisis, psychology has been one of the first scientific disciplines to also take on this idea. Recently, exercise scientists, have made their own calls to adapt and apply similar practices. In a recent preprint, Caldwell and several colleagues make the case for more transparency in exercise science, particularly through preregistration. At the same time, a new Society for Openness and Replicability in Kinesiology was created.

Another advantage of specifically registered reports (in which the protocol is peer-reviewed before the study takes place) is that once the protocol has been accepted, it will be much easier to get the final results published, as this is not conditional on the outcomes anymore (i.e. no more problems with reviewers who argue your work is not interesting because you find non-significant results!).

Is preregistration or writing a registered report a lot of work? When you’re truly doing hypothesis-driven research, we think it is not, as you would have to write down your introduction, hypothesis and methods anyway. So why not do it before your research? With registered reports, you get the added advantage that reviewers can actually help you to improve your experimental protocol. No more “it would have been nice if the authors could have measured x.” We therefore encourage you to have a look at the links provided in this article, and have a go at a preregistered study!

Is exploratory a dirty word in science?

It doesn’t have to be!

Especially when it’s clear to reviewers and your audience which part of the research is hypothesis-driven, and which is exploratory. Registered reports and preregistration can be a great tool in ensuring transparency of your research findings.

Contributors: Sjoerd Bruijn (@sjoerdmb), Alexander Stamenkovic

Copyright

© 2019 by the author. Except as otherwise noted, the ISPGR blog, including its text and figures, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.

ISPGR blog (ISSN 2561-4703)

Are you interested in writing a blog post for the ISPGR website? If so, please email the ISGPR Secretariat with the following information:

- First and Last Name

- Institution/Affiliation

- Paper you will be referencing